Normally I’m quite happy if I don’t get chain invitations to “the ten films that inspired me”, or whatever. However, my brain cells were stirred into action by Fiona Charles’s invitation to nominate seven books that have meaning for me.

Almost as interesting as the selection of the books was musing about how I would select them. What criteria would I use? Should I have a theme, some sort of progression, or simply go for a scatter-gun approach? In the end I chose a few books that had a great influence on me at various stages of my life, spotted a vague theme, and then refined the list to bring the pattern into clearer focus.

I presented the seven books in the order in which I read them, from the age of about nine or ten up to my forties. Five of the books came from my schooldays, and three of them were set books at school.

The first was “Winter Holiday”, by Arthur Ransome. At primary school in south London our teacher would read Ransome’s classic “Swallows and Amazons” to us in chunks and that sent me off to the local library to work my way through all his other books. I enjoyed them all, but the one that really sticks in my memory is “Winter Holiday”. I still have the mental picture I constructed of the setting, a frozen, wintry, Lake District. So engrossed was I that I raced through the book, reading it under the bedclothes with a torch, and some illicit chocolate, long after lights out.

My parents strongly encouraged their children to read avidly. It was obviously in their interests to see lively, potentially mischievous children wrapped up in books, broadening their minds rather than causing mayhem. In those days weekly trips to the library on a Saturday morning, with frequent ad hoc visits on the way home from school, were part of the normal routine for children. “Winter Holiday” is the book that really stands out in my memory from those days.

Book number two was PG Wodehouse’s “Right Ho Jeeves”, which I read about a year before I left primary school. We were on holiday in Pembrokeshire, and my elder brother had borrowed this book from the library. I was intrigued by his laughter, and as soon as he had finished I grabbed the book. I had never before read a book written for adults.

Not only was I entranced by the humour, and by Wodehouse’s astonishing flourishes with the English language, I was excited by the knowledge that adult books were now within my reach and there was a whole new world to explore in the adult section of the library. It was one of the major turning points in my life.

The third book takes that idea a step further.

It is “A Tale of Two Cities” by Charles Dickens. We studied it in the third year of secondary school in Yorkshire. By that time I had read countless adult books but this was my first exposure to a classic of English literature. To my slight surprise this didn’t feel like schoolwork, or any sort of work at all. The book was simply a pleasure, exciting even, to read. High class literature was no longer for other people, for real adults. I knew I could read the great works of my native language and enjoy them.

Number four was also a school set book, “Le Château de ma Mère” by Marcel Pagnol. I took A Level French, which entailed studying serious, heavyweight French classics; Racine, Molière and Balzac. Pagnol’s book, a charming, autobiographical story of life in the south of France before the First World War, is perhaps a French version of “Cider With Rosie”.

It was one of the easier options in the French A Level syllabus and the school used it as a gentle introduction to French literature after the relaxed, frankly easy, O Level.

I came late to the French course, having started A Level Maths and deciding to switch to French after a couple of months. By that time the course had moved on to Racine’s “Andromaque” (Greek tragedy, as interpreted by a 17th century dramatist). I had to catch up and to my surprise zipped through the couple of hundred pages of “Le Château de ma Mère” over a weekend, enjoying it as a book for its own sake, rather than as a necessary chore. When the subsequent fate of the main characters was revealed at the end of the book I was deeply moved. I still remember the phrasing Pagnol used to describe the death of one boy in the war.

In addition to French I also studied German at A Level, and that provides book number five, Theodor Storm’s “Der Schimmelreiter”. This is a dark, atmospheric tale of tragedy, ghosts and rivalry in the gloomy Frisian marshes at the edge of the North Sea.

It was ideal material for teenagers. The other authors we studied were Goethe, Brecht and Kafka. Unlike the French department, the German teachers hit us with the hardcore material right at the start. We were plunged into Goethe’s “Iphigenia auf Tauris” (more Greek tragedy, as interpreted by the pre-eminent 18th century German dramatist). The idea was to weed out the faint hearted while it was still early enough to switch courses. It worked. We lost about a third of the students.

“Der Schimmelreiter” was saved for light (or dark?) relief in between Bertolt Brecht’s agitprop, “Der Gute Mensch von Schezuan” (something of a cheerfully Communist pantomime, to be fair), and Franz Kafka’s resolutely incomprehensible short stories. As with “Le Château de ma Mère” I read “Der Schimmelreiter” for pleasure, the first book I could read in German and simply enjoy without thinking about coursework and exams.

The sixth book is Jan Morris’s “Spain”, which was written in 1964 when the country was still very much in the grip of Franco’s dictatorship. I read it some 20 years later when Spain had already changed dramatically, but I was fascinated by the evocation of the country and its insights into a troubling recent past. The book triggered a lasting love of Spain, that has lasted over the decades especially after I married Mary, who shares my love of the country.

The final book is quite different from any of the others. It is Zygmunt Bauman’s “Modernity and the Holocaust”. Bauman was a sociologist and his book is deeply troubling for those who still have the comforting illusion that modernity and sophisticated civilisation will lead to humane outcomes.

Bauman argues persuasively that the Nazis’ Final Solution to exterminate the Jews required a sophisticated, bureacratic, modern society to organise and carry out industrial mass murder and that it is a huge mistake to assume that the Holocaust was a throwback to uncivilised barbarity.

What the Nazis did was certainly barbaric, but it was the product of civilisation and modernity. It might seem irrational, but only if you have a different world view from the Nazis. They rationally followed the logic of their evil philosophy through to its appalling conclusion. We have not “progressed” beyond the Nazis. They don’t belong to a state of civil development and progress we’ve left behind. Given the right circumstances it could all happen again.

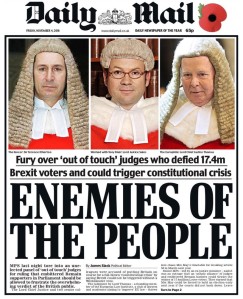

As a Christian I conventionally have a bleak view of the fallibility of human nature. We are all fallen sinners. Bauman’s narrative reinforced that wariness. Technology, civil order, civilisation, intellectual sophistication are all good things, but they won’t save us from tyranny and horror, or even from ourselves. They can be turned to horrifying ends in the wrong hands. Bauman’s book is always nagging away at the back of my mind when I see in our society signs of fascism, extremism, bigotry, intolerance or indifference to the sufferings of “others”. These feel like the real political and social threats we face.

My selection of books consciously reflects my upbringing and the way that my education shaped me. I was at four schools, one in Stirling, two in London, and one in Yorkshire. Starting in Scotland, and being brought up in a Scottish family, mean I am and I feel unquestioningly Scottish. But the English education and friendships left deep and welcome marks. The way our family moved around the UK, and my immersion in French and German culture, opened my eyes and my mind.

If someone asks “what is your home town?” I shrug and can’t answer. I have no home town. Perth is my home, and I love it, but my character was set before I moved here. I knew virtually nothing of the city till I arrived in my mid 20s. My upbringing means my world is inevitably much wider than that.

Culture, art, literature are valuable because they enhance humanity – not because they represent the best from our own little patch. I am a citizen of the world. I could have been no other.

In Theresa May’s eyes I am a citizen of nowhere. When she used that phrase at the Conservative Party conference of 2016 it cut deep. I have no home town.

“If you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere.”

May was appealing to the least attractive elements of her own party, trying to establish her credentials as a zealous convert to the Brexit faith. She probably didn’t really mean it, but that made it all the more wounding. The serving Prime Minister was prepared to sneer at people like me, to dismiss us as losers who should have no say in the future of our country, in order to strengthen her position within her own party. It was as bleak a moment as I have known watching British politics.

There are unpleasant, dark trends in western society. Populists are making common cause with nativist isolationists, xenophobes and outright racist bigots. They hate the values that underpin what is decent in our society while paying lip service to its traditions. Many of them proclaim their Christianity, but the reality is they wear their faith lightly, as a mark of the tribe rather than a sign of inner humility, love and awe.

To people like me the EU was never simply a trading relationship. Far more than that it embodied a major part of our identity. I am Scottish, British and European. Brexit not only tears away part of my identity, it trashes it. I feel rejected by what should be my own country.

My seven books range from classics of English (the nation, not the language) children’s literature, English humour and perhaps Britain’s greatest novelist, to fine books from France and Germany, a beautiful invocation of the mystery of Spain and conclude with Bauman’s terrifying warning. These are books that have shaped me and my world view. I can only look in dismay at the way that the UK is moving.

Citizen of the world? Yes, I am, and that won’t change however much damage the Brexiters do to the economy, society and our place in the world. When I was at school in London I was gripped, along with my friends and brothers, by the amazing saga of the Apollo missions that culminated in the first moon landing in 1969. Exactly 50 years ago, on Christmas Eve 1968, this photo was taken, Earthrise. It’s hard now to convey the shock and excitement of that moment, seeing our planet like this for the first time. This blue and white blob in space is our home. We are its citizens. That sense of awe, and belonging, won’t go away.